Rare UK Ride-on Mowers

January 3, 2026 in Articles, Machinery

No matter what someone collects, there’s always that one item or model that proves elusive – and garden tractors and ride-on mowers are no exception.

Over the years, I’ve come across makes and models of ride-ons that seem to have vanished completely from the UK, with no surviving examples known to exist.

You might expect that, with today’s internet, social media, online auctions, and marketplaces, even the rarest machines would eventually reappear. But that’s not always the case.

I’ve compiled a list of “unaccountable” models in the UK – machines that, as far as I can tell, have disappeared. For this blog, I’ve chosen just five that might still be hiding somewhere, perhaps forgotten in a shed or under a heap of scrap.

So, what exactly is an “unaccountable” machine? My definition is simple: these are models that were definitely sold or imported into the UK when new. Photographic evidence of their presence here, or trade or test reports done in the UK with physical machines is always great. But also newspaper adverts and show coverage, and also useful are UK price lists and specific UK brochures.

Listed in date order, the five models I’ve chosen are: the 1961 Gemco Reelrider, the 1964 Gravely Westchester, the 1966 Bolens Suburban, the 1973 ATCO Atcomatic, and the 1985 Westwood Lawnrider.

Somewhere, perhaps, one survives in the UK…

1: 1961 Gemco Reelrider

The USA-made three-wheel 24” Deluxe Gemco Reelrider was advertised in UK newspapers in the early 1960s. Adverts also appear for second-hand models, so some must have been sold from new. F. H. Burgess, Burton Road, Lichfield, was one of the retailers.

The Gemco mowers were made by the General Mower Corporation – hence where the Gemco name comes from – based in Jefferson Avenue, Buffalo, New York. USA.

The Reelrider was built around a tubular steel frame, running on 10” semi-pneumatic puncture-proof tyres. It had a 2 ¾ hp Briggs and Stratton engine through a v-belt clutch to a chain drive.

The rear 24” cylinder mower had five tempered alloy blades, and was mounted on self-adjusting bearings. The cutting height could be varied from 7/8” to 2 and 1/8”.

2: 1964 Gravely Westchester

The USA-made 1964 Gravely Westchester four-wheel tractor is an interesting machine. It could be bought in the UK in the mid-1960s.

The Westchester was based on a Gravely two-wheel walk-behind tractor. This meant that several of the front-mounted attachments for the walk-behind would also fit the Westchester as front-mounted implements, including mowers, a snow blade, a sprayer, and a snow blower.

The Westchester was designed by the Studebaker car company, which owned Gravely. It had fibreglass body panels, a Gravely single-cylinder 12 hp engine, and an 8-speed transmission, similar to the two-wheel model, but it featured rear axle steering.

Several UK dealers are mentioned as selling the Westchester, including J. H. Hancox Ltd, Solihull. The importer was Belos Gravely Ltd, Seghill, Northumberland, who listed it in their literature with UK prices.

It would be assumed that the four-wheel Westchester would be a better solution than the two-wheel with a sulky seat attached – but for some customers it wasn’t. According to Gravely, they agreed to buy back Westchester models from unhappy customers, with many subsequently upgrading to the new 1967 four-wheel Gravely 424 tractor. I wonder if this was the fate of the Westchesters in the UK?

3: 1966 Bolens Suburban

Bolens imported a vast range of ride-on mowers and garden tractors to the UK. However, the 1960s Suburban, which is well documented in the UK, seems to have vanished with no examples appearing to have survived on these shores. In 1968 the new Suburban was advertised at £230.

The Suburban was a basic ride-on mower, powered by mid-mounted 4 or 5 hp Briggs and Stratton engines with a mower deck directly underneath. They have basic tiller steering, but do have pneumatic tyres and sprung and padded seats.

In the mid-1960s, the revised white-painted Suburban (earlier models were painted gold-coloured), was well advertised in newspapers, including photographs of the Suburban in UK showrooms. They even appear in the television series ‘The Prisoner’ filmed outside at Portmeirion and indoors at MGM Studios at Borehamwood between 1966 and 1968.

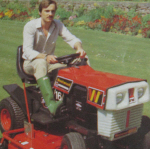

4: 1973 ATCO Atcomatic

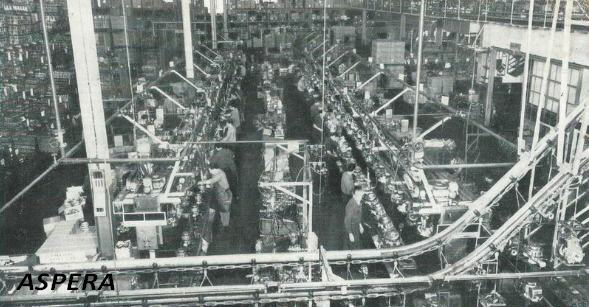

In 1973, ATCO introduced the Atcomatic rear-engine riders; they were on sale for a few years.

The models were the 26” cut 7 hp 726E electric start and 726R recoil start, and the 32” cut 8 hp 832E. All had forward and reverse hydrostatic drive.

It is currently unknown where the Atcomatic was manufactured; the use of Briggs & Stratton engines often points to the UK or the USA.

Brochures, price lists, adverts and second-hand adverts exist for the Atcomatic, yet no examples of these mowers have reappeared from the back of sheds or garages.

After being discontinued, in 1980 ATCO started importing lawn tractors made by Dynamark in the USA, branded as ATCO. Then, in 1986 until 1992, ATCO manufactured in Stowmarket the familiar classic design dark-green tractor models.

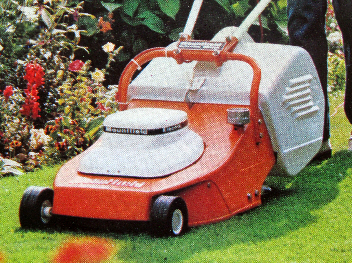

5: 1985 Westwood Lawnrider

Westwood designed, made and imported a range of ride-on machines, but one model has remained elusive: The Lawnrider.

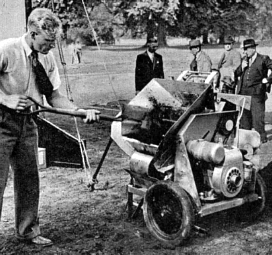

The only photo that seems to exist is on the right, from a 1985 trade report.

The UK-made Lawnrider was announced in 1985. It was to be a revolutionary rear-engine rider encased in a wrap-around body shell. It had an electric height adjustment for the 25” rear-discharge mowing deck, and an integrated rear collector and rear roller.

Models were equipped with 6 hp Tecumseh or 8 hp Briggs & Stratton engines. Prices started at £691.

However, although appearing in trade reports as ready-to-go products with prices, it’s possible that none were sold. But optimistically, there may be one or two test models lurking out there.

This model perhaps led to the creation of the 1990 Westwood Clipper rider – although that was another unusual model which had a limited sales life.